On the eve of D-Day, General Eisenhower sent to each of the soldiers, sailors, and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force a letter of encouragement from which I have taken the title of this post. How difficult it must have been for him to send forth so many young men into such great danger. Eisenhower spent that last evening with the men of the 101st Airborne and stayed until the planes had all disappeared into the dark night.

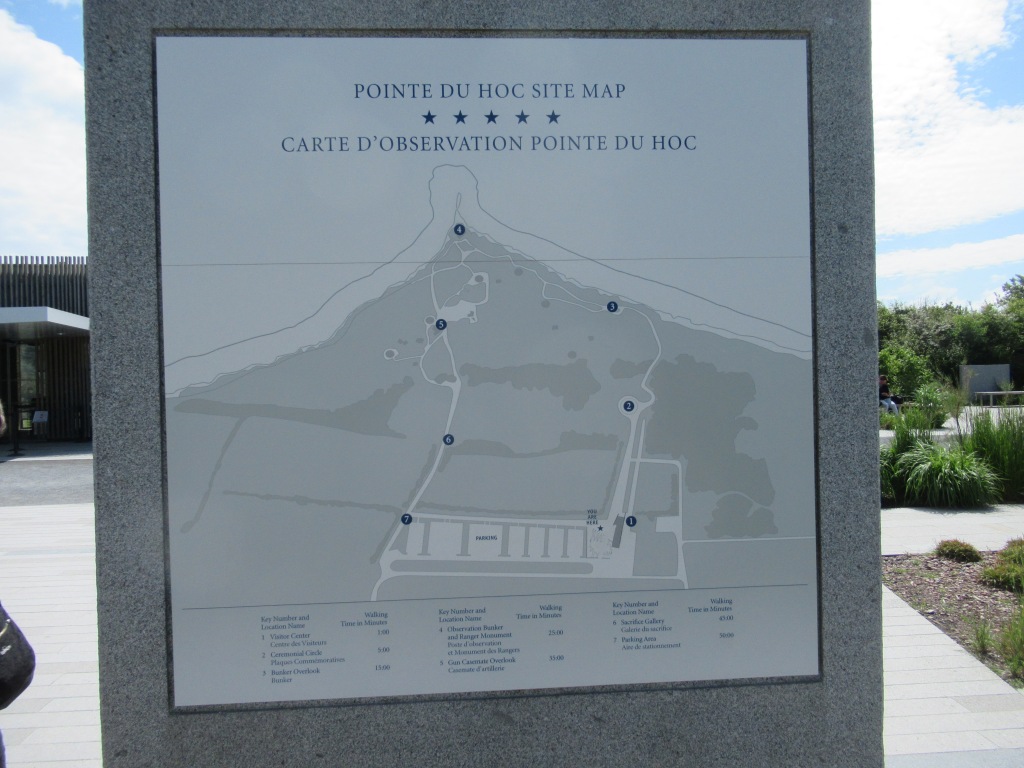

I collected a delicate, perfect seashell (as I had at Utah Beach) to add to our jar of seaglass back home. From here, we drove to the top of the 90-foot cliffs at Pointe du Hoc, where Army Rangers once achieved the impossible, under fire.

The Normandy sites come alive through many personal stories, though tens of thousands will forever remain untold. Here is just one: “June 6, 1944 was Sergeant Geldon’s third wedding anniversary. He and his fellow Rangers sang songs to celebrate the occasion shortly before landing on Omaha Beach. The 23-year-old steel worker from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, was cut down by enemy fire within a few minutes of coming ashore. When his widow died in 2002 at age 78, she was buried by his side.”

There are ups and downs to being here now, as June 6th fast approaches. An unbelievable number of active and retired military, as well as a stunning array of vintage Jeeps and other Army vehicles have gathered. The spirit of anticipation and brotherhood are at their highest. However, much of the American cemetery was blocked off, including the main memorial visible in the opening photo, with its soaring statue representing American youth. We never learned if there were open sections toward the back where you could walk among the graves. Thus, we were very grateful to find the Garden of the Missing open and paid our respects amid its tranquil beauty.

The story of the day would not be complete without mentioning our brush with the gendarmerie. At what appeared to be a random police checkpoint, Lance briefly considered making a run for it in our Range Rover (thinking of the movie The French Connection) when an officer waved him in. Better judgement prevailed, though, and after a very careful scrutiny of Lance’s driver’s license, we were free to go find lunch. We did not observe a single other vehicle get pulled in. On a lighter note, rambling the countryside has surely been a highlight, knowing that the churches, stone houses with their tile roofs and flower draped walls, even the hedgerows, must be little changed from 1944.